Downloads

“Of all the components of soil, organic matter is probably the most important and most misunderstood. Organic matter serves as a reservoir of nutrients and water in the soil, aids in reducing compaction and surface crusting, and increases water infiltration into the soil. Yet it's often ignored and neglected.”

Eddie Funderburg, Senior Soils and Crops Consultant, Noble Research Institute

“However, as soil organic matter decreases, it becomes increasingly difficult to grow plants, because problems with fertility, water availability, compaction, erosion, parasites, diseases, and insects become more common. Ever higher levels of inputs—fertilizers, irrigation water, pesticides, and machinery—are required to maintain yields in the face of organic matter depletion. But if attention is paid to proper organic matter management, the soil can support a good crop without the need for expensive fixes.”

Fred Magdoff and Harold van Es | 2010 Building Soils for Better Crops, Third Edition

These are a couple of quotes from academic literature about soil organic matter. What they basically say is that the organic matter level in a soil is a good indicator of the health of that soil, the life in that soil, the plants that grow from it and the animals (including us!) who eat those plants. When it comes to nutrition, biodiversity, ecology and the long term future of the human race – soil really matters.

Over and above all of that, soil organic matter contains carbon. If you can increase the organic matter in your soil, you are reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, and that helps with our fight against climate change.

When I came back to our family farm here in south west Scotland, after ten years in agricultural consultancy, I followed the standard route towards farm intensification. After becoming disillusioned with that, after seven or eight years, we began our journey towards organic and agro-ecological farming. I learned from the pioneers in this form of farming about building soil health and productivity through enhanced soil organic matter. It took many years before we really started to see results, but now we carry as much stock on our farm as we did 25 years ago, but without all those toxic agri-chemicals and fertilisers.

Around that time I took over the sampling of farm soils from the fertiliser company reps, because I had been trained to do this professionally. Soil sampling was important because I wanted to be certain that we had a reliable, independent assessment of our soils’ fertility. All samples were taken from at least 10 or 20 sample points in each field and sent to The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research in Aberdeen, later taken over by the James Hutton Institute in Dundee.

In those days I was only interested in the main nutrient levels in the soil, organic matter wasn’t even on the radar. However, thankfully, the Macaulay tested all the soil samples at that time for soil organic matter and that was kept on record. It really wasn’t until 6 or 7 years ago that I began to specifically ask for the soil organic matters to be tested because that was being seen as an important part of our soil health and carbon emissions data for the farm. By this time an extra charge was being made for organic matter testing, which I kind of baulked at, but this was important so I coughed up.

About a year ago I heard that there might be organic matter data being held on our soils at the James Hutton Institute and I thought it would be interesting to see what changes, if any, had occurred in our soil organic matter during our transition to organic and ecological farming.

It took about 9 months to find the data because it was held in old system files that required expert IT support to open. With a bit of kind insider help from a farming researcher, we finally got the data and analysed it. What it showed was very exciting.

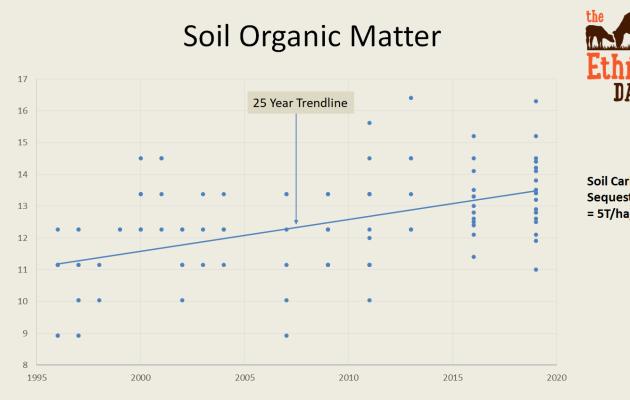

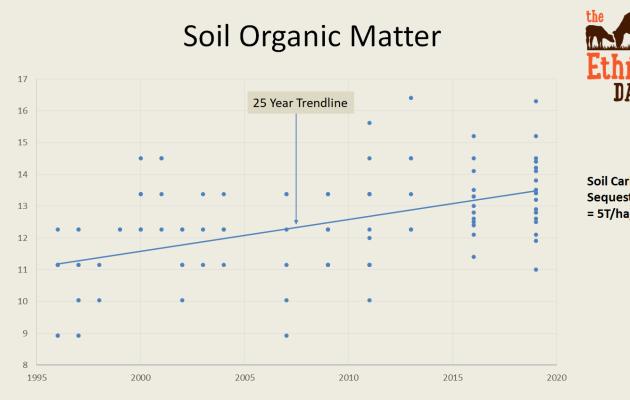

Improved grassland soils in the west of Scotland usually vary between 6% and 12% organic matter. Twenty-five years ago our soils averaged around 11% organic matter but, by 2019, this had increased to almost 14% organic matter.

Once we had applied the science and done the maths, consulted with experts, allowed for possible unknowns and cautiously rounded down estimates, we concluded this meant our soils were locking up over FIVE TONNES of carbon per hectare every year.

At the same time, we’ve been analysing how much carbon our farm emits into the atmosphere, which works out at around 3½ tonnes per hectare every year. So, we’re not just producing food – meat and dairy – with no impact on the climate. It’s actually benefitting the climate. It CAN be done.

We are confident that our 25 years of soil data shows that our farm is carbon negative, and in fact is sequestering substantially higher levels of carbon than commercial forestry could achieve. We don’t need wall-to-wall forestry to achieve our climate targets. Regenerative and agro-ecological food production can deliver the same climate benefits but with additional biodiversity benefits and rural job creation. In fact, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the wrong trees in the wrong places can do more harm than good from a climate and biodiversity point of view.

At a conference held on our farm a year and a half ago a soil scientist suggested that the science seems to be ten years behind innovative farm practice and, dare I say it, government policy is probably ten years behind that. There is very little good data at practical farm level on the effects of ecological farming on soil organic matter and, therefore, carbon.

To help rectify this we are making our 25 years of soil data publicly available to any scientist anywhere in the world who is interested in reviewing it - open-source farm data, if you like. The full data set can be downloaded in the link below.

If we are going to meaningfully tackle climate change, biodiversity loss, food security and a host of other issues facing society, we need our scientists to study what is actually happening in the real world, and we need our policy makers to be in that loop and understand the importance of practical, lived experience. We want to be part of the solution in exploring how our food systems can deliver an ecologically sound planet. We hope our soil data is helpful in making that happen.