There’s a lively debate going on in the food world just now about how we address the complex and inter-connected range of challenges facing society. It’s known as ‘Sparing or Sharing’.

The Sparing argument goes something like this; if we concentrate food production on the best land and maximise production from that, we can free-up enough marginal land for re-wilding to offset the environmental impacts of intensification. This is the argument promoted by the agri-tech industry and is supported by a number of scientific papers. It is plausible and attractive to much of the influential food and farming industry and, as such, is attractive to policy makers.

The counter argument, Sharing, goes something like; if we move to an ecological system of food production we can produce enough food to feed the world while, at the same time, minimising the negative social, welfare and environmental impacts. This scenario involves using natural processes and management techniques to replace, or partly replace, fertilisers, pesticides, anti-biotic, etc. This ecological approach is more complex and difficult to implement and would be economically damaging to the agri-tech industry. While some NGOs and a majority of the public would prefer this approach, powerful food industry interests would make every effort to block it.

So these are the two main offerings. Hi-tech, high input with re-wilding, or ecological farming working alongside nature.

The Sparing argument is seductively simple. More of the same but more focussed.

Worryingly, there have been two or three fairly high profile papers published in recent months supporting this approach, and they have been promoted heavily by vested interests.

However, I see a number of major flaws in this argument:

- Much of the current rural social and environmental mess we are in has resulted from the industrialisation of food production, is doing more of the same really going to solve anything?

- The misery inflicted on the animals and the work-force in these intensive systems is rarely mentioned.

- The dependence of industrial farming on technologies that are creating future threats, such as anti-biotic resistance, pesticide resistant super-weeds/pests and resource depletion, should be a grave concern.

- The fragility and vulnerability of these systems to geo-political shock and consequently the threat to national food security.

- Sustainability, because when the land that is supporting this industrial system of farming does finally burn out, what then? Research suggests we’ve as few as 30 harvests left. There is no planet B.

Thank goodness then for the publication yesterday of the UN’s IPBES global assessment report for policy makers on biodiversity and eco-system services. It covers every aspect of our lives and their impact on our environment, both on land and at sea, and it makes for pretty grim reading.

The report comes down firmly in the Sharing camp and it makes clear that we are running out of time. Our high input food production systems require fundamental, transformative change which, it points out, will be resisted by vested interests.

It emphasises the need to incentivise innovative, sustainable, regenerative and ecological farming. It recommends the dis-incentivisation of pesticide and fertiliser use and the implementation of the principle that the polluter should pay.

Currently society picks up a lot of the externalised (consequential) costs that arise from industrial farming systems – anti-biotic resistance, pesticide and fertiliser contamination of drinking water, climate change and much more. In other words, there’s no such thing as cheap food – someone always has to pay.

I very much welcome this report. Things need to change, and they need to change urgently.

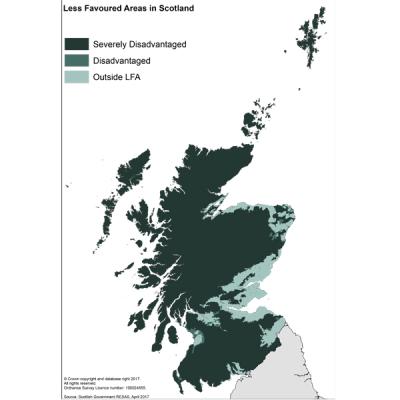

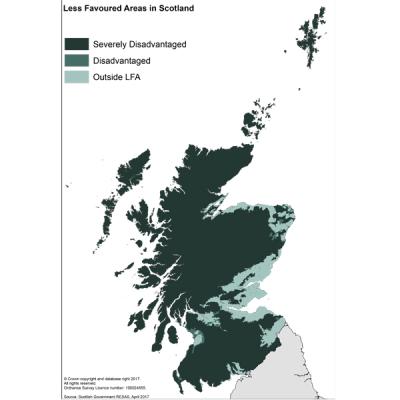

As a farmer in the south of Scotland, a country renowned for its natural grass-based livestock systems, the opportunity to take the lead in incentivising regenerative and ecological farming is a no brainer. 85% of Scotland’s agricultural land is officially classified as ‘less favoured’ agriculturally (see below). Many of those farms in the ‘severely disadvantaged’ and ‘disadvantaged’ areas are already farming ecologically or could transition to agri-ecological farming relatively easily.

Government and farmers should be allies in furthering an approach to farming that works with our natural assets rather than against them; pioneering a pasture-based, regenerative approach that is as sustainable as it is productive. Intensification plus rewilding might sound like an easy option, but the UN’s IPBES report makes clear that it’s the wrong option.

The youngsters in our society are taking up the call to action. Power to their elbows! It is now time for our leaders to step up and implement the changes humanity needs to deliver a habitable world to future generations. Fundamental to that change is how we produce nutritious food for our children and grand-children without wrecking their planet.

These are complex, interconnected problems that require a systemic rethink of our whole economy. Next week we are hosting a small conference that brings together experts in regenerative, ecological farming. The IPBES report makes these discussions more important than ever before. The time for change is now.